————–

Disclaimer: Selecting merely ten issues from the multitude of foreign policy challenges Brazil faces is, of course, a rather impossible task, and bound to omit crucial topics. The list below therefore does not claim to be complete (it does not contemplate key topics such as climate change, development aid, non-proliferation, the WTO and the Middle East), but seeks to stimulate the debate about a challenging year ahead. Comments (preferably of the critical sort) are, as usual, most welcome.

————–

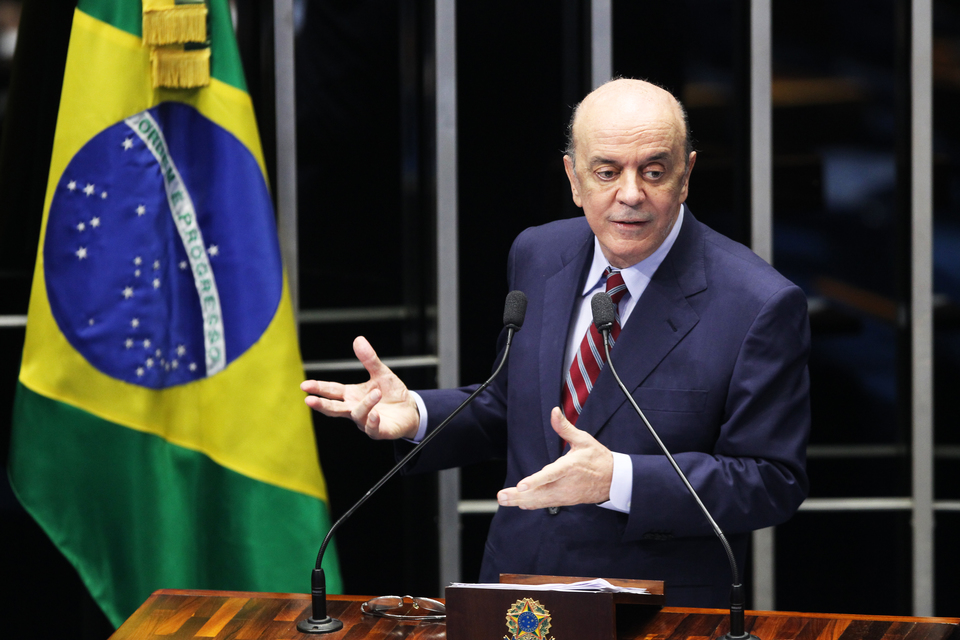

Brazil’s foreign policy under its three former Presidents — Fernando Henrique Cardoso (1995-2002), Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva (2003-2010) and Dilma Rousseff (2011-2016)— was, despite some setbacks, shaped, above all, by the challenges of managing Brazil’s rise and transformation into a modern, globally visible actor. The interim government led by Michel Temer, by contrast, seeks to arrest Brazil’s decline as Latin America’s largest economy enters what may become the fourth straight year of near zero or negative growth. This requires updating some of the key tenets of Brazilian foreign policy, while maintaining others. Above all, considering the extremely limited time Temer remains in office and the fact that 2018 will mostly be dedicated to campaigning (with his Foreign Minister José Serra, pictured above, expected to run for president again), foreign policy makers will have to pick their battles wisely. Below are ten key challenges they will face over the coming twelve months:

————–

1. Help accelerate Brazil’s economic recovery

Brazil’s economy is in tatters and no foreign policy in the world could fix it without profound domestic reforms, some of which are already taking place. And yet, a wisely designed foreign policy can make an important contribution. That implies reviving Mercosur (suspending Venezuela was a good start) and actively pursuing free-trade agreements, making BNDES’ foreign lending more transparent and effective, solving the outstanding double-taxation issues through bilateral agreements, and clearly articulating to international investors how Brazil seeks to get out of the economic mess (a plan to move up 30 spots in the World Bank’s Doing Business Ranking would be a good start). It also includes aggressively seeking funding from the BRICS-led New Development Bank, restarting the scholarship program for Brazilian students abroad (but limiting it to engineers), facilitating immigration rules and actively attracting skilled migrants (from places like Syria) and slashing cumbersome visa rules to double the number of foreign tourists. By the end of 2017, Brazil should no longer be the most inward-looking economy of the G20, a position it occupies today.

2. Develop a regional long-term strategy vis-à-vis Venezuela

The political, economic and humanitarian crisis in Venezuela presents the greatest challenge to South America in years. With the Venezuelan government now essentially in the hands of the military, Brazilian foreign policy must focus on damage control; i.e. reduce large-scale human suffering in the neighboring country. A significant part of the population is no longer having three meals a day. Public hospitals across the country lack even basic medicines. Looting of supermarkets is becoming more common. People with chronic diseases that require medication are forced to emigrate if they want to survive. Brasília should therefore lead an international effort to put pressure on the Maduro government to allow the delivery of basic medicines to hospitals across Venezuela. Addressing the humanitarian crisis is not only morally compelling, but also in Brazil’s national interest: the longer the problem festers, the greater the risk of civil strife in Venezuela, which could create instability on a regional scale. At the same time, Brazil should continue attempts to isolate Venezuela diplomatically in an effort to force Maduro to accept free elections. Rather than “solving” the region’s Venezuela problem, policy makers will for now have to content themselves with administering it. It will be left to Temer’s (and Serra’s) successors to find a lasting solution.

3. Manage the global corruption fallout

Termed the “biggest international bribery case in history” by the US Department of Justice, corruption related to Odebrecht’s global operations have cast a shadow over Brazil’s international reputation, and Brazilian foreign policy makers will have to deal with the enormous backlash of the international dimension of the Lava Jato investigation in the coming months. Politicians in several countries consider being associated to the company as toxic, and Panama and Colombia have recently conditioned the company’s continued presence on better cooperation by Odebrecht with criminal investigations. Peru said it would no longer work with the Brazilian company after it had “corrupted three Peruvian governments.” One of the best ways to reduce the fallout is to actively show the world how Brazil has embraced tougher anti-corruption legislation and how it is able and willing to take a lead in international efforts to curb corrupt practices. That involves promoting the debate on this topic on the big stages in 2017: the World Economic Forum in Davos, the International Security Conference in Munich (Embraer is also embroiled in bribery cases), the G20 in Hamburg, the 9th BRICS Summit in Xiamen, Mercosur and UNASUR meetings and the UN General Assembly in New York. Temer could also convene a specific meeting of regional heads of state to discuss devising a common strategy on the matter, such as more data-sharing and training for public prosecutors (which are weak and not independent in several South American countries). This not only produces benefits for Brazil, but for the international community as well, considering that the United States’ role in the global fight against corruption may change under President Trump.

4. Explain Brazil’s unique moment to the world

Brazil is going through a unique moment in its history. While many business sectors and state bureaucracy had a a close and often incestuous relationship for the past 500 years, these practices are no longer workable as the Lava Jato investigation is altering the way politics and business works, possibly forever changing public tolerance of corruption. Understandably, this has temporarily paralyzed several key actors, who have to learn how to engage properly, with negative short-term economic consequences. Foreign policy makers must show international observers that this is, above all, a positive development, as it will make Brazil, in the end, a more modern, transparent and democratic society. Only if this is communicated successfully will investors from around the world help Brazil recover from its worst recession in history.

5. Prepare for a more Asia-centric world

China may grow somewhat slower than before, but few would seriously dispute that we are witnessing a momentous shift of power to Asia. The world economy will not return to the distribution of power of the late 20th century, and Asia’s weight will make itself felt in every aspect of global affairs. Brazil’s embassy in Beijing has grown over the past years, but the number of diplomats in other key locations like Tokyo, Delhi, Manila and Hanoi is still too low. After all, it is in these countries that the most important dynamic of the 21st century (a growing clash of interests between Washington and Beijing) will play out. Embracing a more Asia-centric world cannot be done by the Foreign Ministry alone — Brazilian universities, newspapers and companies are an essential element in this reorientation. Being a founding member of the China-led AIIB and actively involved in the BRICS grouping are important steps in the right direction.

6. Design a strategy to address violence at home

In 2015, a staggering 58,383 people were assassinated in Brazil. The number of murders in Brazil increased over 250 percent in the last three decades, jumping from 13,910 in 1980 to above 50,000 in 2012. This means that one person is killed in the country every nine minutes, or 160 per day. Since there is little hope for systematic progress on the domestic level, diplomats can work towards creating international rules and norms with teeth and building momentum that will, in turn, increase the pressure on domestic actors to adapt to regional or global standards. A first step would be promoting gun registration on a regional scale and strengthening cross-border cooperation. Despite an existing set of regional agreements, the majority of the millions of firearms in Brazil are not registered, and though most are produced in Brazil, they are often sold abroad and are then smuggled back into the country.

7. Recover Brazil’s voice in global security matters — by starting at home

When it comes to the dominant themes in global security over the past twelve months, such as the civil wars in Syria, South Sudan, Afghanistan and Ukraine, the global refugee crisis or terrorism, Brazil has rarely gone beyond the role of a bystander, ceding airtime to traditional powers. Yet Brasília could be far more pro-active in the global discussion about how to effectively address the challenges listed above, and positively influence dynamics —as it has done, in the past years, regarding humanitarian intervention, internet governance, peacekeeping, conflict resolution and defending democracy. That requires, first of all, being in the room when such things are discussed — such as at the yearly Munich Security Conference, where Brazil too often has been absent in the past years. That also involves prioritizing security issues at home. Brazil largely fails at managing its borders and the security threats that emanate from it, related to the smuggling of people, drugs and arms. Brazil is now a key base for drug traffickers, and the country must establish a better strategy to cooperate with neighbors in addressing organized crime in the region.

8. Tackle growing challenges in cyberspace

New communication technologies erode hierarchies, collapse time and distance, and empower networks. That will have a massive impact on international relations, and cybersecurity will be a key element of foreign policy making in the coming decades. Issues that define cybersecurity today — such as incident response, the problem of attribution, overlapping investigative and legal authorities, public-private partnerships, and the necessity of international cooperation — are much-discussed in Washington, Berlin, Moscow and Beijing, but Brazil still lacks the expertise to play a key role in the global debate about the rules and norms of cybersecurity. The same applies to international relations scholars at Brazilian universities and think tanks, which remain largely unprepared to weigh in on the issue. To provide an example: The German defence ministry has stepped up its electronic warfare capabilities with the creation of a new 13,500-strong cyber unit, to be operational in 2017. The issue already produces real challenges the Brazilian government has failed to tackle effectively. Brazil is one of the world’s leaders when it comes to hacking and online fraud. Yet rather than militarizing the issue, the government should lead a global debate on how to create international frameworks to help achieve a safe cyber realm — e.g. by helping train a growing number of specialists in government, the private sector and civil society is essential to achieve this aim.

9. Strengthen BRICS, revive IBSA

Contradicting all expectations of the imminent dissolution of the group, the BRICS member countries have worked towards strengthening cooperation for one decade. The BRICS not only continued to exist but also started a process of institutionalization, leading to regular ministerial meetings in areas such as education, public health and national security, frequent encounters between presidents and foreign ministers and – perhaps most importantly – the creation of the BRICS-led New Development Bank (NDB), headquartered in Shanghai, and the contingent reserve agreement, a financial safety net for times of financial crisis. The BRICS summit is now a major pillar of the yearly travel schedule of the nations’ presidents, irrespective of ideology. Brazil should promote a broader debate about how it can benefit from the grouping ahead of the 9th BRICS Summit in China. Parallel to the BRICS grouping, the government should consider reviving the IBSA grouping. Despite the current political crisis in Pretoria, South Africa will remain an important partner, and India will shape the global economy of the 21st century like few other powers.

10. Continue to work towards reforming international institutions

Why should Brazil care about reforming the UN Security Council in times like these? The answer is simple: Because global responsibilities are not a function of fluctuating growth rates at home. There is little use for a country that engages constructively on international issues in good times, only to disappear when the economy is not doing so well. That is why Brazil’s diplomatic retreat under Dilma Rousseff has been so damaging: The moment a future president will adopt a more visible international role, it will make international observers wonder whether this is just another fluke. The logic of why international institutions such as the World Bank, the IMF and the UNSC need reform remains as valid as ever, and Brazil’s crisis does not alter the overall trend of multipolarization.

Read also:

How Trump Benefits China in Latin America (Americas Quarterly)

International Politics in 2017: Ten Predictions

Is This the End of US Soft Power in Asia?

Photo credit: psdb.org.br